The Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors on Tuesday took the first step in crafting rules governing Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS), giving their unanimous approval to a draft ordinance that aims to give a measure of local control to new facilities.

The ordinance before the board includes safety rules such as requiring 100-foot setbacks from agricultural land and 1,000-foot setbacks from “sensitive receptors” such as schools, daycare centers and residential care facilities.

It limits height of the facilities to 25 feet, requires the batteries to be contained in single-use buildings or lockers and requires enhanced fire alarms, air quality monitoring and annual training for staff.

In addition, the draft ordinance prohibits nickel-manganese-cobalt chemistry in new battery systems, which was in place at the Vistra plant in Moss Landing when it caught fire on Jan. 16, spewing black clouds of smoke for three days.

But instead of rubber-stamping the ordinance that was before them, the supervisors added several of their own requirements, and directed staff to return on Jan. 13 for review.

This includes water, soil and air analyses, developing ways in and out for first responders during emergencies and using skilled, local labor.

In addition, staff should look for ways to stop water runoff from the facility to protect local watersheds, the board said.

The board also directed staff to identify the potential costs of potential BESS failures

If the board passes the ordinance, it will then go to the Community Development and Infrastructure Department for environmental review. It is expected to be approved next year.

County Executive Officer Nicole Coburn told the board that the ordinance will give local officials some control over any new facilities, which are largely regulated by the state.

“The purpose of this is to develop a local ordinance so that we maintain local control over siting and operational requirements of the new facility,” Coburn said.

County officials warn that, without a new ordinance in place, developers could bypass local approval and apply directly to the state, which would bypass local regulations.

“Without a Santa Cruz County ordinance in place, our community would be subject to the decisions of state agencies resulting in a significant loss of local control,” Assistant Planning Director Stephanie Hansen told the board.

BESS facilities, which store energy from green energy sources such as wind and solar, are an integral part of the state’s mission to break away from reliance on fossil fuels, Hansen said.

The county’s 2022 Climate Action and Adaptation Plan estimates that 52,000 megawatts per year will be needed for such a transition.

“Successful transition away from fossil fuels is not possible without storage,” Hansen said.

Supervisor Justin Cummings said that the main issue is maintaining local control of new BESS facilities.

“This is another type of technology, this is another type of industrial development that we really need to maintain control over to make sure that when it’s implemented, it’s going to be at the highest safety standards that will meet the needs of the community and reflect the values of the community,” he said.

John Swift, a representative from New Leaf Energy—the company hoping to build a BESS facility on Minto Road—said the facility will be a boon for the county during power outages.

“This can supply energy for over 200,000 homes in case of an outage,” he said. “Mitigating the surges and problems with energy distribution is a very local advantage.”

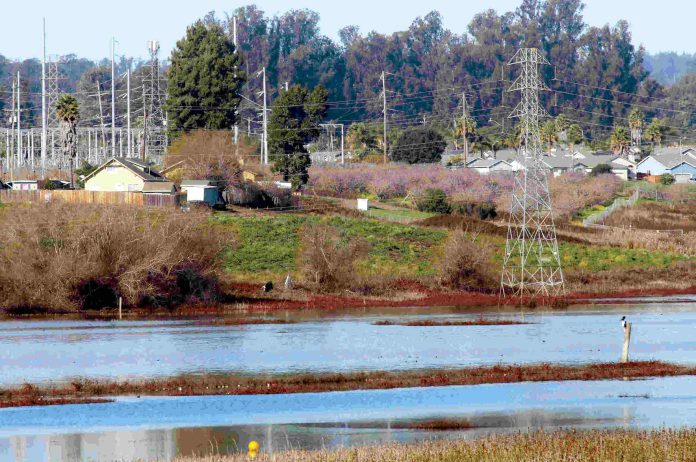

Supervisor Kim De Serpa expressed concern that the proposed facility on Minto Road is three-quarters of a mile from a school and near residential areas.

“It’s literally in a neighborhood, right behind a neighborhood,” De Serpa said.

Still, De Serpa acknowledged the need for local rules.

“I don’t want the state to go ahead and rubber-stamp this,” she said. “There hasn’t been a single project that has gone to the state that has been denied. All of them have been approved.”

Supervisor Monica Martinez said that the draft ordinance is not the final version and that the county still has time to shape it before it gets final approval next year.

Martinez added that the county should look for ways to mitigate costs of environmental safety testing and emergency responses by requiring developers to foot the bill.

“I would like it to be crystal clear that whatever we can legally recover from these costs we are doing so,” she said.