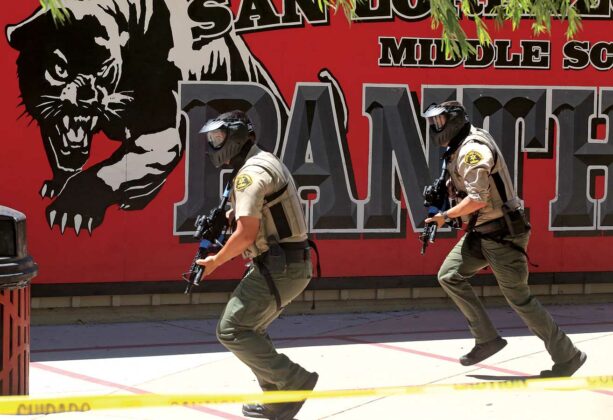

For five days last week, Watsonville Police Department officers joined police, firefighters and medical professionals from around the county—and beyond—in active shooter training, running through policies and live scenarios at the San Lorenzo Valley Unified School District tri-campus in Felton.

Sgt. Mish Radich, who headed up to the North County for professional development on July 13, said it was great to see public safety officials practicing how to respond effectively to an increasingly prevalent problem facing American communities.

“We train in schools, but this can happen anywhere—at a large business or a large office,” he said. “We’ve had them happen around us.”

Watsonville Police responded to the shooting in Morgan Hill in 2019 that killed two Ford dealership employees; the department also provided mutual aid during the Gilroy Garlic Festival shooting that killed three victims and left 17 others injured, the same year.

While de-escalation was part of the training, Radich noted the drills focused more on how to neutralize a shooting suspect who is causing an immediate threat and how to quickly organize treatment for victims amid chaos.

“That’s not a time to de-escalate,” he said. “It’s valuable training and, unfortunately, in the United States it’s something that’s picking up—not just school shootings, but also the mass shootings.”

The good thing is that Santa Cruz County does have plenty of fire and police agencies that can spring into action, but personnel need to be ready to act, Radich adds.

“We have the resources on duty,” he said, noting after the drills at the SLVUSD campus officers went through debrief sessions. “It’s great training.”

During last year’s active shooter drills, which were held at Scotts Valley High School, an actor made a comment that was interpreted as a potential threat, which led to an hours-long hunt for possible danger.

The silver lining to that disruption was that it proved quite the learning experience, remembers Scotts Valley Police Department Capt. Jayson Rutherford.

“We got to see firsthand how well different agencies can come together, quickly establish command and mitigate a threat,” he said. “It also increased our security measures at the training site and our screening procedures for role players.”

According to Rutherford, that incident wasn’t the reason for the venue change.

“We wanted officers to experience a different location to respond to,” he says, noting all SVPD patrol staff and detectives signed up this year.

Lt. Nick Baldrige of the Santa Cruz Sheriff’s Office explained that getting all the players working together ahead of a critical incident is crucial.

“The faster we can provide treatment, the more lives are gonna be saved,” he said, noting there were 24 volunteers in attendance on July 14 to help make the scenario feel realistic. “This has evolved, just as law enforcement’s response to mass shootings has evolved.”

Around the time of the 1999 Columbine High School massacre, police were taught to follow the surround-and-call-out model, where police create a perimeter and attempt to contact the suspect with the help of tactical officers.

A Colorado commission recommended a change in practices, where the initial responders are sent into harm’s way more quickly.

“There was a transition,” Baldrige said of the move away from surround-and-call-out. “It was the tactic they had at the time, because this wasn’t really a thing pre-Columbine on the level we have now.”

According to Pew Research Center data, there were three active shooter incidents (categorized by the FBI as “one or more individuals actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a populated area”) in 2000; that rose to 61 in 2021.

Locally, active shooter training began in 2013, with Nathan Manley, a campus police officer at UC Santa Cruz, heading it up.

Manley now works in the private sector in Silicon Valley, but his mass violence response organization (IMVR Group) has been providing consulting services to the Sheriff’s Office, which took the reins this year.

For a while, the “diamond formation” was the go-to technique, said Baldrige.

“You would have a person in the front, a flank on each side and then a rear guard,” he said. “You’d need four (officers) to be able to move that way.”

This presented problems for rural locales such as Felton.

“You think about using this as a scenario—the San Lorenzo Valley—it could take a little bit to get that fourth person here,” he said. “If you’re having to wait … we’re losing lives. And so now it’s transitioned into: You hear gunfire, you go towards gunfire. And you try to neutralize that threat as quickly as possible.”

There’s been a shift in how firefighters respond to active shooters, too—moving away from a more passive role during the early moments of a response.

“Historically, we ‘staged’ for incidents where there was any sort of threat,” said Zach Ackemann, deputy director of IMVR Group. “However, we realized, in recent years, that there was a need to get advanced care to the patients as soon as possible.”

By July 14 at least 435 participants had gone through the classes, which included sessions for hospital staff and 911 dispatchers.

Andrew Dally, the Capitola Police Department chief, said from his perspective active shooter training must continue to happen annually, at a minimum.

“In incidents such as an active shooter, multiple agencies from this region will respond,” he said. “These officers will have to work together, and having this type of training allows us to train together—and with similar tactics—which will provide the path for future coordinated responses.”