Editor’s note: This is the second entry of a weekly four-part series about the Pajaro Valley’s Japanese community. The series will culminate on Aug. 14, coinciding with this year’s celebration of the Obon Festival, a cultural and religious Japanese event honoring one’s ancestors. Read the first entry in the July 24 edition of the Pajaronian.

By Hugh McCormick, Special to the Pajaronian

WATSONVILLE—By 1940, Watsonville’s “Nihonmachi,” centered along Union and Main streets, had become a hotbed of Japanese culture, catering to local Nikkei (Japanese emigrants and their descendants who reside in a foreign country) farmworkers and their families. There were kendo and judo dojos, boarding houses, a much-used community center (Toyo Hall), a Buddhist temple, Japanese language schools, pool halls, a photo studio, an ultra-popular baseball field and a variety of shops, laundries and markets, including humble Yamashita Grocery.

Then disaster struck—erasing decades of optimism, hope and progress almost overnight. On Feb. 19, 1942, President Roosevelt released Executive Order 9066, calling for the immediate roundup and internment of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans. The United States was at war with Japan, and President Roosevelt deemed all Japanese people were the enemy.

With flowing white hair tucked under a black and yellow “Watsonville Wildcatz” hat, a blue face mask to complement his neatly ironed periwinkle shirt, and bright, kind and wise eyes, 84-year-old Mas Hashimoto remembers the moment well.

Slowly moving his right index finger up and down the rows of faded pencil-drawn names on two ancient framed maps of what was once Watsonville’s Japantown—his town—Hashimoto says, “There’s an expression ‘Shikata ga nai,’ it can’t be helped. Japan made war with the United States. There are some things you have no control over.”

Hashimoto was only 6 when war broke out—quickly and permanently uprooting his, his family’s (mother, father and six brothers) and his community’s lives.

The old Buddhist temple that once sat on Union Street. — courtesy of the Pajaro Valley Historical Association

Forced to quickly liquidate everything they could not carry with them (homes, cars, land and farms) close to 1,300 Nikkei emigrants living in Santa Cruz County were forcibly relocated and “interned”—first to a temporary camp on the “Rodeo Grounds” in Salinas, and then to Arizona’s Poston Camp II.

In the early months of 1942, there was a whirl of frenetic activity, and at times panic, as Pajaro Valley’s Japanese population prepared to move to an unknown destination. There was a massive surge in marriage license and birth certificate requests as families did anything and everything they could to ensure they stayed together in the months (and years) ahead. Vultures hovered throughout Watsonville, snapping up goods and precious heirlooms for pennies on the dollar. With no idea where they were heading, many Japanese families used the little money they could scrape together to buy quality, warm clothing.

The decline of Pajaro Valley’s once-flourishing Japanese community was precipitous and brutal.

“They were limited to so many pounds of luggage. No pets. They had no idea where they were going so they tried to be ready for any/all climates. Since most farmers did not own the land they farmed but leased it, they had to put their equipment on the market. Usually getting 10% of its value, if that,” said Sandy Lydon, Historian Emeritus at Cabrillo College.

The economic losses—personal and real property—were staggering. But many Japanese also lost one-of-a-kind, irreplaceable photos, family histories and historical artifacts during the war. Some families actually destroyed them themselves, burning piles of journals, photos and other documents to avoid unwanted future attention from the U.S. government and FBI.

In its April 30, 1942 issue, The Pajaronian reported “By noon Thursday, no person of Japanese ancestry remained in Santa Cruz County for the first time in more than a half-century.” There were no trials, no lawyers and no due process of law—despite the fact that 71% of the Japanese were U.S. citizens.

“It was a matter of race, pure and simple,” Lydon said. “The Japanese were identifiable, lived in close proximity to one another, and there were organized groups that wanted them gone. They were just too good at farming and distributing. Too organized. Pearl Harbor provided an opportunity to do what the West Coast non-Japanese competitors wanted all along.”

As Arizona’s Poston Camp II was being built, Watsonville’s Japanese families spent tenuous months corralled at what the government called an “Assembly Center.” The Japanese called the makeshift camp on Salinas’ “Rodeo Grounds” a “Temporary Detention Center.” In reality, it functioned as a prison.

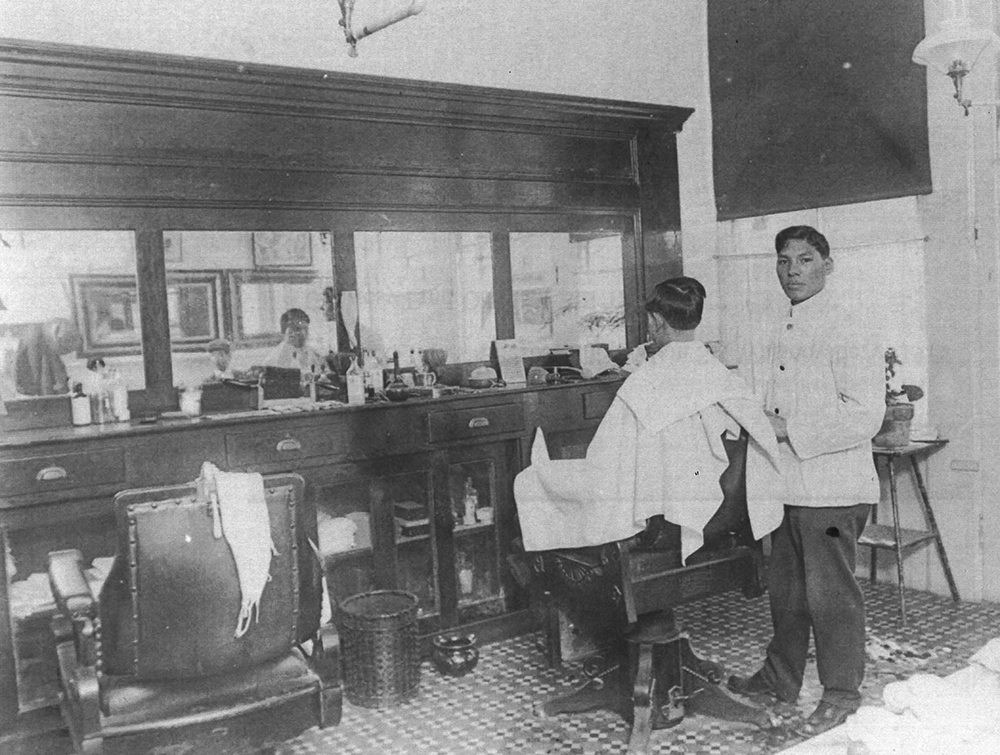

Tokuzo Oda’s barbershop on Main Street, circa 1915. — courtesy of the Pajaro Valley Historical Association

With no formal restrooms, raw sewage flowed freely in open trenches throughout the camp. Families huddled together in hastily-constructed wooden barracks, or in tenements formerly used for livestock. Cold showers were available—but men, women and children were forced to bathe together in military-style gang units. The Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA), the agency in charge of the center’s day-to-day operations, made it a mission to keep personal privacy—and hope—to a minimum.

The center served as an important transition period for the Central Coast’s Japanese population. It was a (somewhat brutal) wake up call that prepared them for incarceration, and life in their final destination.

The WCCA eventually shipped the new inmates to southwestern Arizona Poston Camp II, home to one of the 10 “Relocation Centers” the U.S. government constructed to house the Japanese for the duration of the war.

At its peak, Poston housed over 17,000 inmates, making it the third-largest “city” in Arizona. In terms of area, Poston was the largest “concentration camp,” as some Americans and most Japanese called them, operated by the War Relocation Authority during WWII.

The hastily-constructed, uninsulated barracks made of tar paper and redwood cracked and shrank under the desert sun and 120 degree heat. Each relocation center functioned as its own town—with a post office, schools and farmland for keeping livestock and growing food. But there was a constant shortage of basic supplies, including lumber, food and clothing.

Without adequate nutrition, many inmates at Poston began to lose weight and wither away upon arrival. Outbreaks of disease, including tuberculosis, were common occurrences in the concentration camp. Periodic dust storms brought with them fainting spells, bloody noses and heat rashes. With limited access to medical supplies, many Japanese inmates died of preventable causes.

As their bodies buckled in the brutally hot summer afternoons, and frigid nights, tensions and frustrations at the Poston slowly crescendoed. The lack of food, medicine, clothing, the armed guards and the miles of razor-sharp wire that stretched to the horizon began to take its toll.

Some inmates became angry and bitter toward the government and the camp’s operators. Why were Japanese Americans singled out, incarcerated and caged while other enemies of the country, namely German Americans and Italian Americans, were allowed to remain free? Yet many Japanese, Hashimoto said, still pledged their allegiance to the U.S.

“They asked us loyalty questions,” Hashimoto said. “Like ‘will you take up arms if ordered?’ and ‘will you swear allegiance to the United States and not the Emperor of Japan?’ My mom told us to answer the questions ‘yes, yes.’ Most Watsonville families answered this way.”

Just a month after President Roosevelt announced that the “military necessity” of camps like Poston no longer existed in December of 1944, the Supreme Court issued a formal ruling—Endo v. the United States—which would lead to their eventual, and permanent closures.

Following the decision, Supreme Court Judge William Francis Murphy voiced his criticism of the Japanese internment writing, “I am of the view that the detention in Relocation Centers of persons of Japanese ancestry regardless of loyalty is not only unauthorized by Congress or the Executive but is another example of the unconstitutional resort to racism inherent in the evacuation program.”

In the early months of 1945, after three long years of living in an atmosphere of fear, despair and suspicion, Pajaro Valley’s Japanese population was free to go home.

•••

In next week’s entry, the Pajaro Valley’s Japanese return home and try to rebuild.