WATSONVILLE—Louis Braille introduced a new way of understanding the world when he created his original tactile writing system in 1824. After losing his sight as a child, the Frenchman developed the first form of the code at the age of 15.

Versions of the system are still being used today—including locally within the Pajaro Valley Unified School District’s Visually Impaired (VI) Program, headquartered at Watsonville High School.

During a recent meeting, board members voted unanimously to reclassify longtime PVUSD employee Alejandra Rocha’s position within the VI Program as Alternative Media Specialist. Rocha will focus on creating media—including braille translations—for the 50 or so students in the district who require it.

“We get instructions from our students about what they need,” Rocha explained, “and we work from there. Anything that can better help them access their school work, whatever they need adjusted—we will do it.”

Rocha has worked for PVUSD since 2000 in Special Education. A few years ago, she met a former VI teacher who asked if she’d be interested in working with the program.

“At that time, I didn’t know braille or what this program did,” Rocha said. “But when I learned more, I knew I wanted to be part of it.”

For the past few years, Rocha has worked on perfecting her skills. She has taken online classes and worked one-on-one with other translators. It has not been easy, she admitted.

“With braille… you’re learning an entirely new alphabet,” she said. “There’s a lot of technology involved, too. It took me a while to learn everything.”

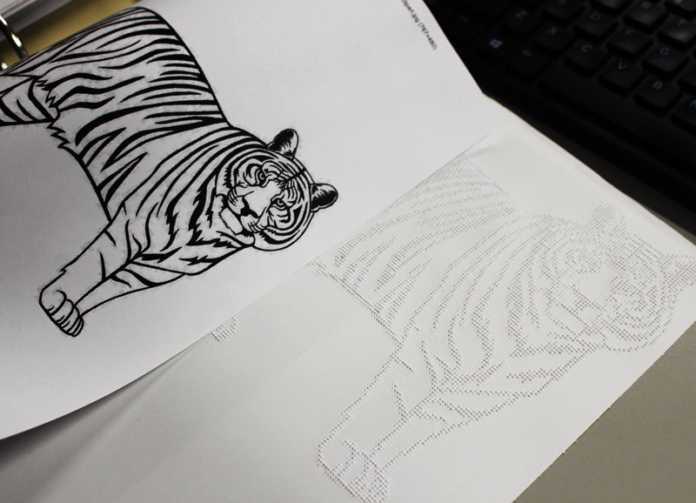

Rocha creates media with Nemeth Braille (math) and braille literacy—two completely different systems. She translates images; everything from drawings of animals to constellation maps. Mechanical devices are used, including a braille typewriter, embossers and a thermoforming machine. Computer software helps immensely, but digital translations still need editing, Rocha said.

Alternative Media Specialist Alejandra Rocha explains how to use a mechanical braille typewriter. (Johanna Miller/The Pajaronian)

“It’s about attention to detail,” she said. “It needs to be correct. Accuracy is key.”

Rocha also resizes type to larger print—something that is not “one size fits all,” she said.

“Everything I do is according to the needs of each student,” she said. “Some need specific point sizes. Some math graphics are very simple, others aren’t. We have an advanced math student right now who needs far beyond the basics. We do everything for him by hand.”

The VI Program was originally part of the Santa Cruz County Office of Education’s Special Education Program. Eventually, PVUSD created its own Special Education Local Plan Area (SELPA), which allows the district to support its students exclusively.

Rocha works out of a small office at Watsonville High School with two VI teacher, Alexis Hawks and Kathie Reynolds. The teachers filled positions in the department that opened up at the end of last year.

As a VI teacher impaired, Hawks visits schools and works with each student directly.

“Some of them are independent, and others need a bit more help,” Hawks said. “It’s different every day. You never know what you’re going to do.”

Reynolds, who already had a VI credential and retired from the program, returned this year, bringing experience to the new team.

Hawks said there are some misconceptions about what they do.

“People think we read braille by touch,” Hawks said. “But we actually read it like an alphabet, with our eyes. Learning by touch is incredibly difficult. Students who lose their sight when they’re older… it’s harder for them.”

Rocha said the reclassification of her job signals the growth of the VI Program.

“I’m just happy that I can help students access their work,” Rocha said. “I’m glad that they’re comfortable coming to ask for help. I want to keep learning so I can support them even more.”